Gallery

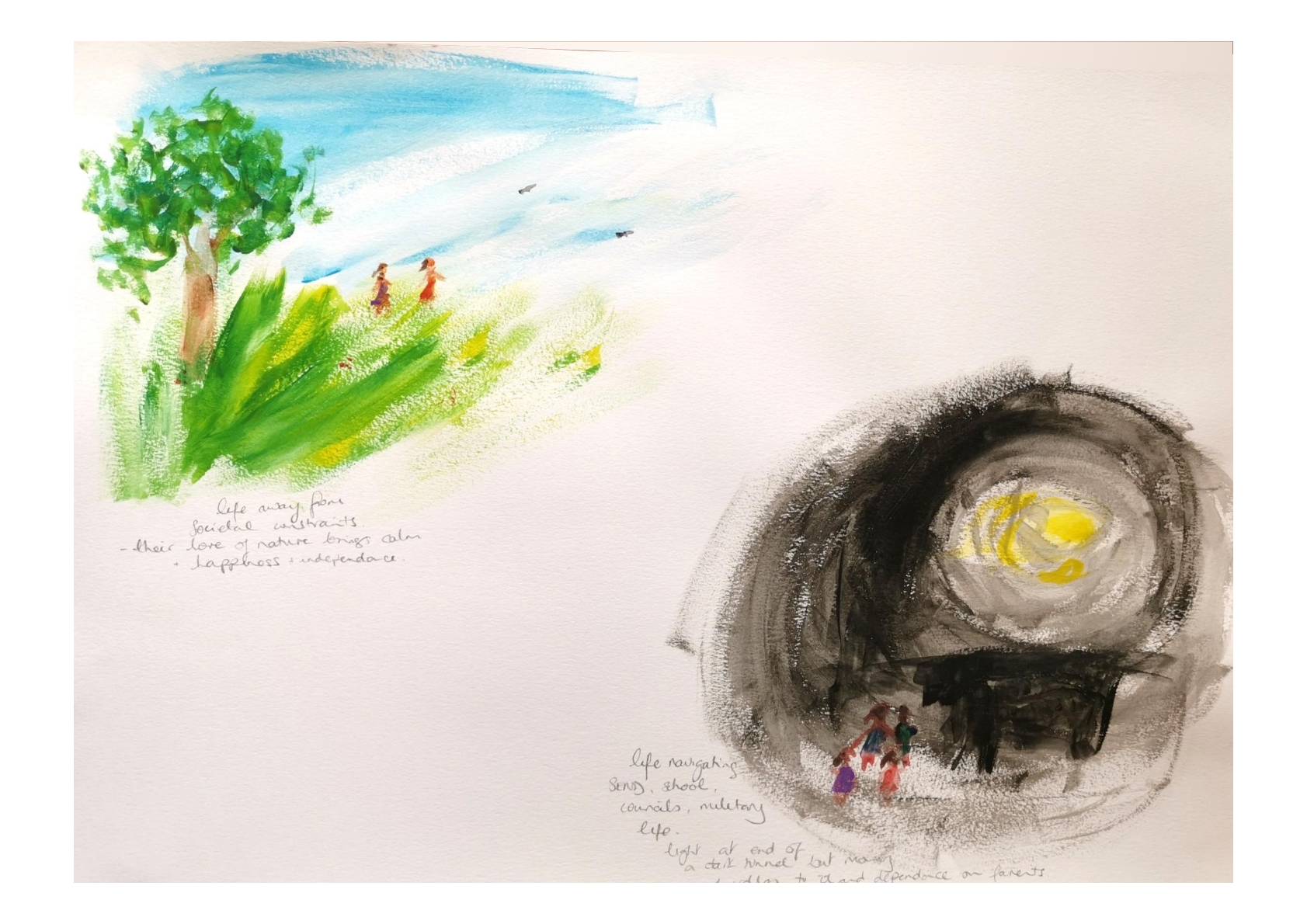

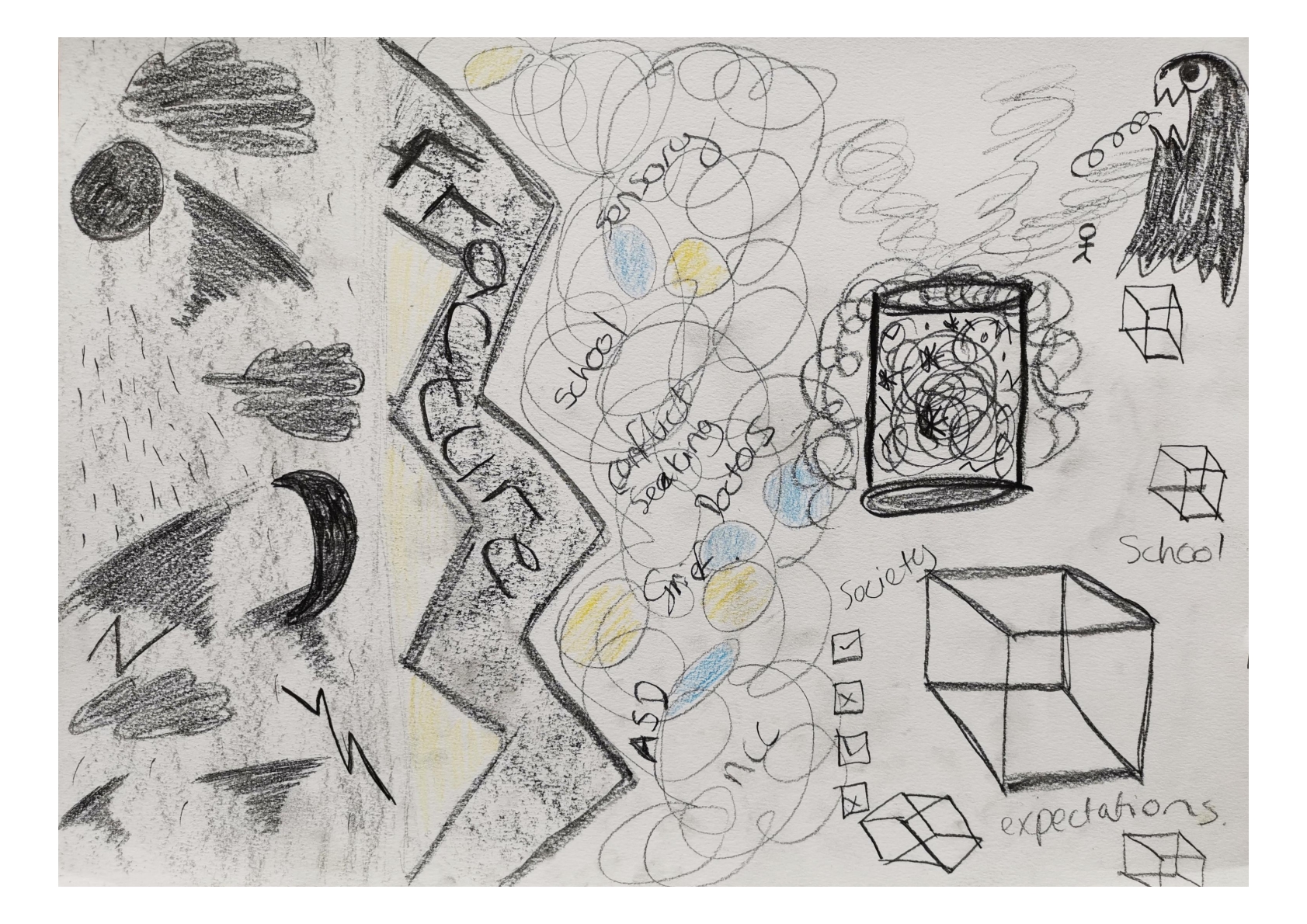

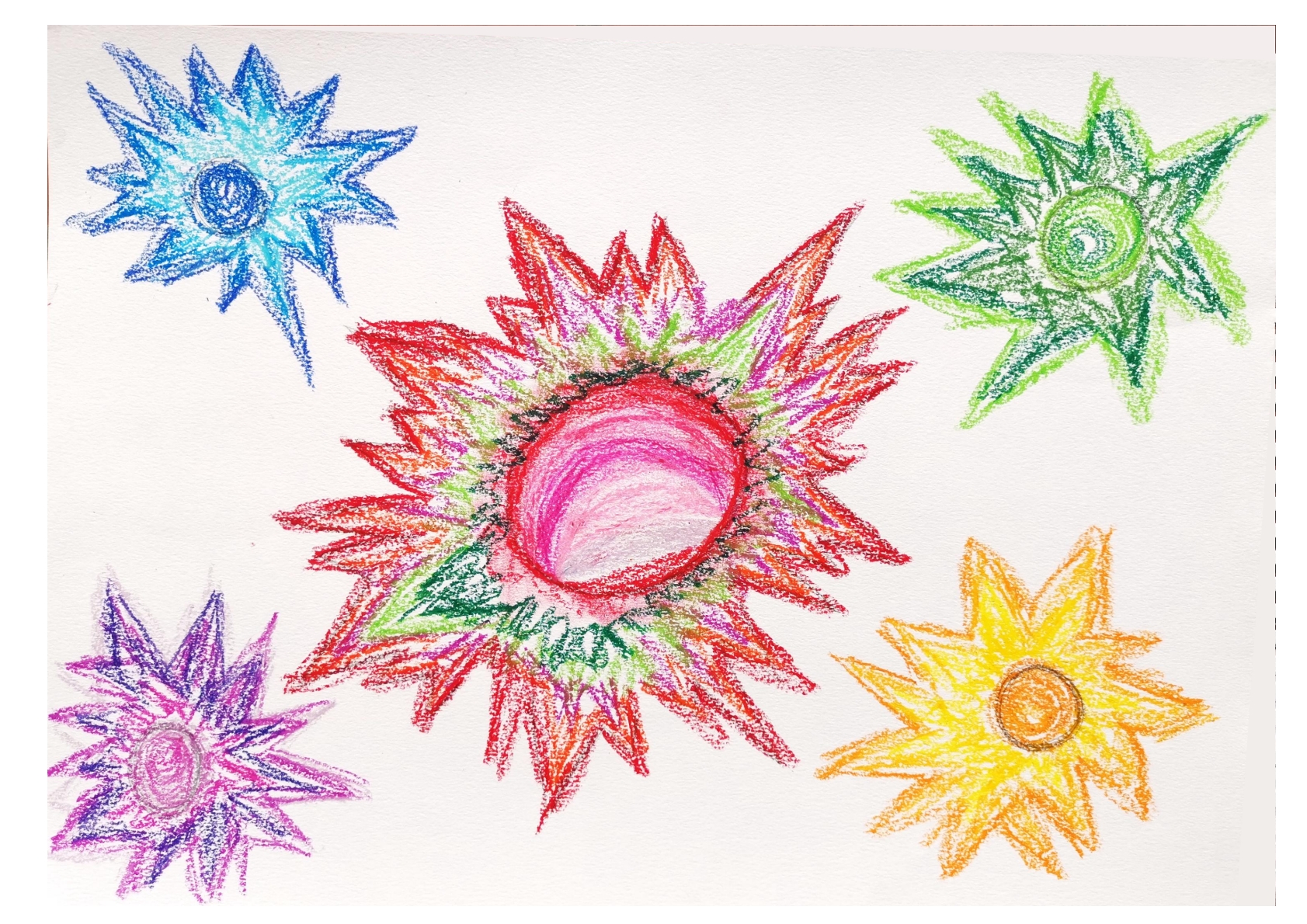

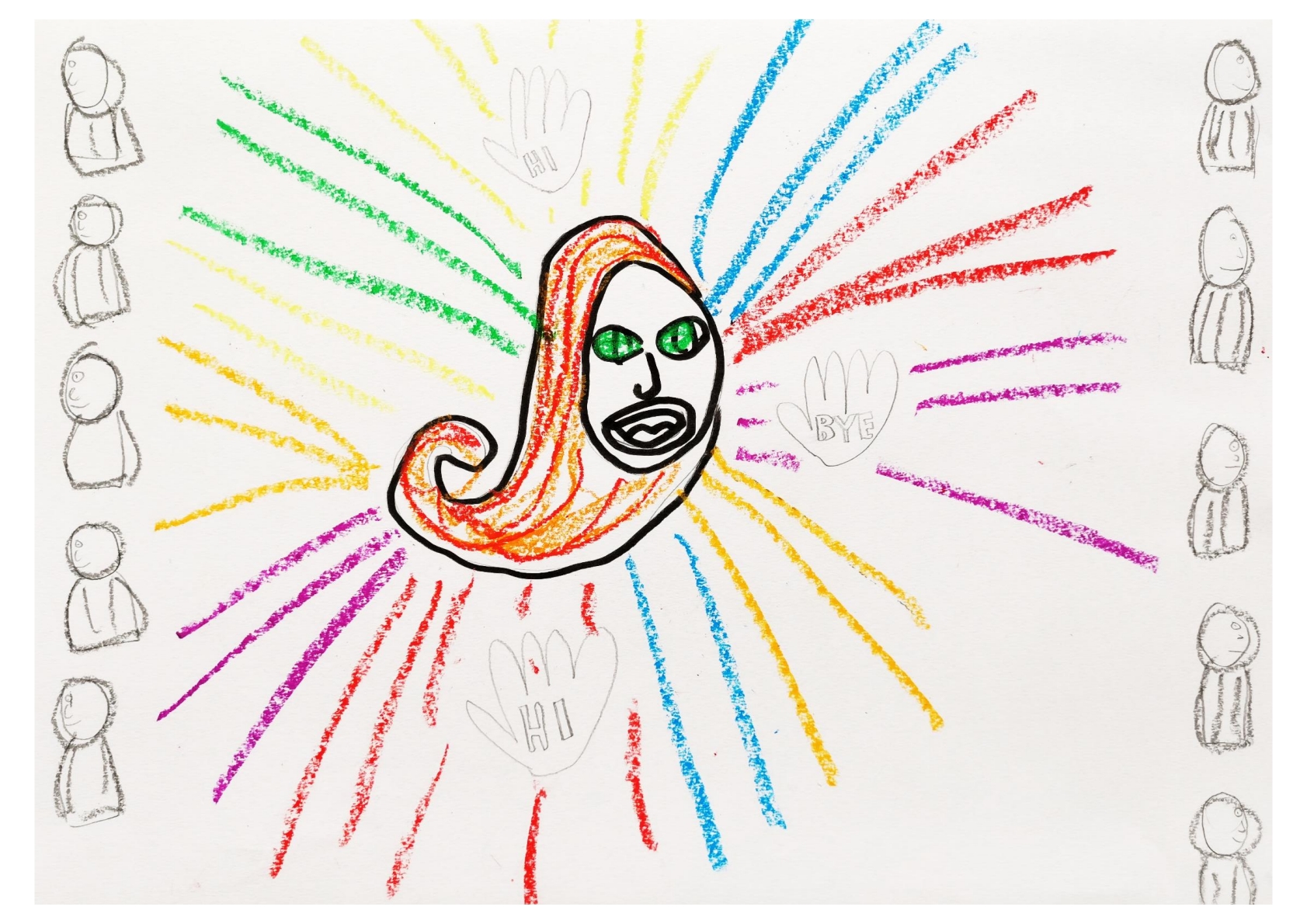

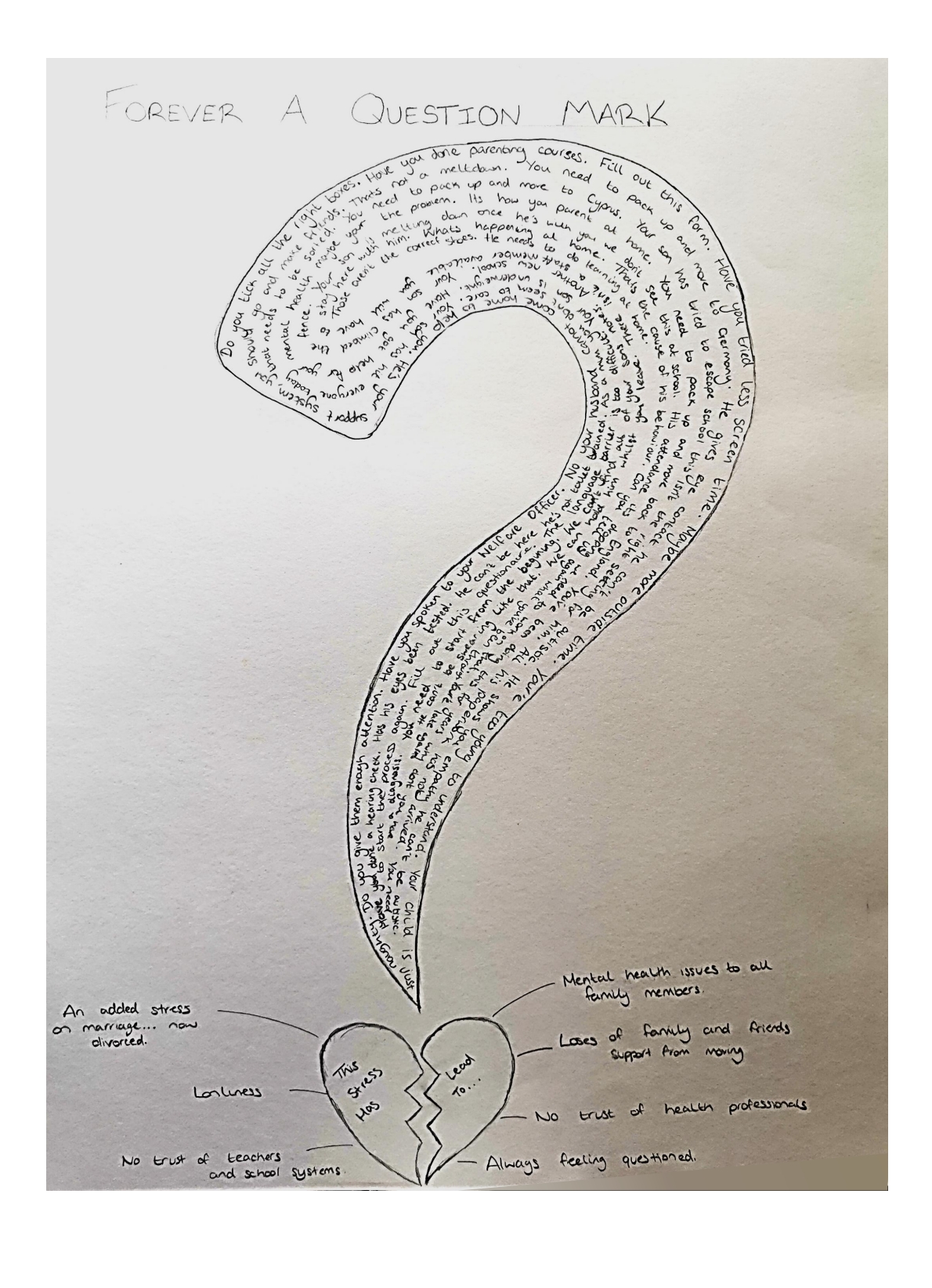

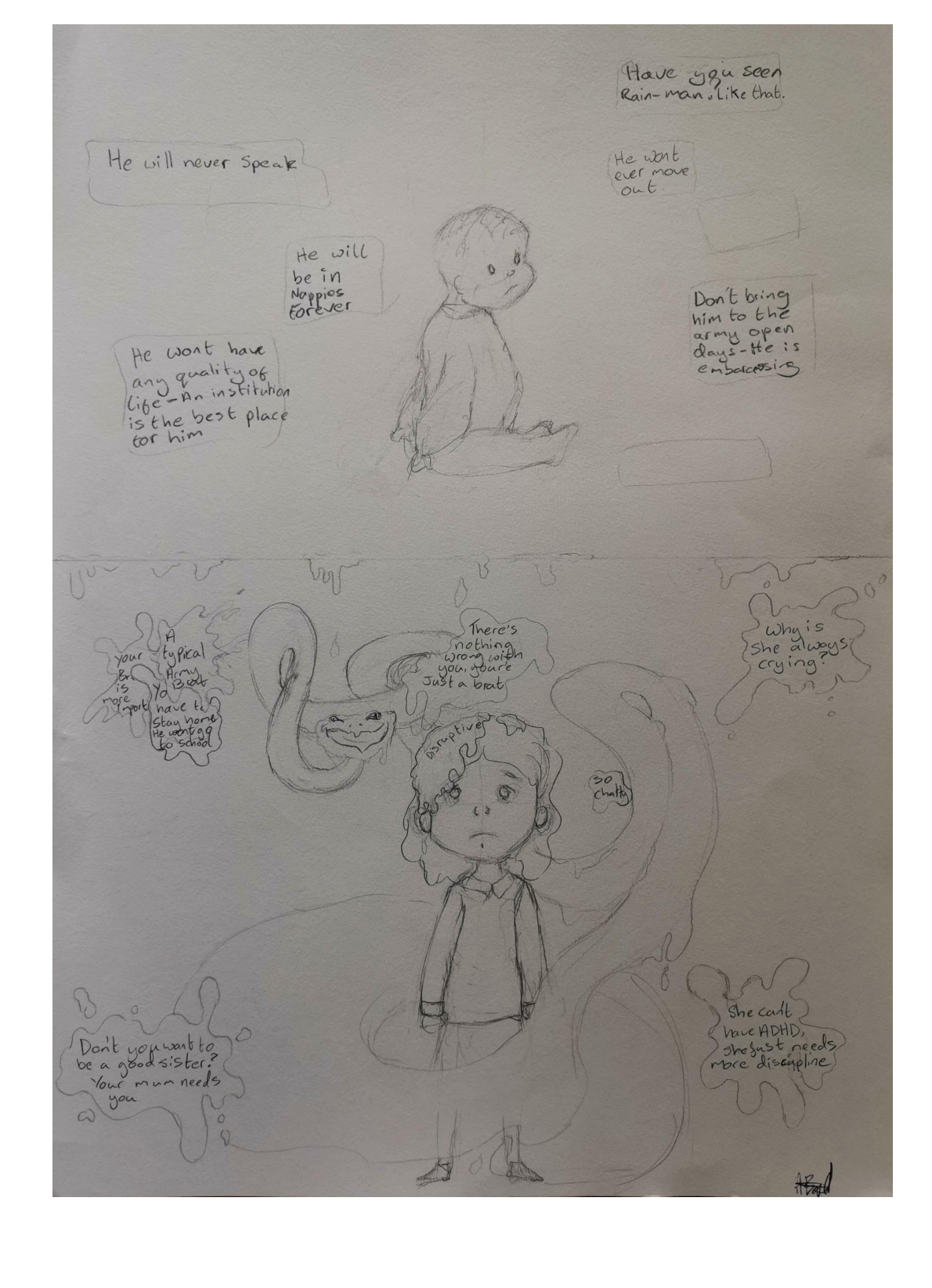

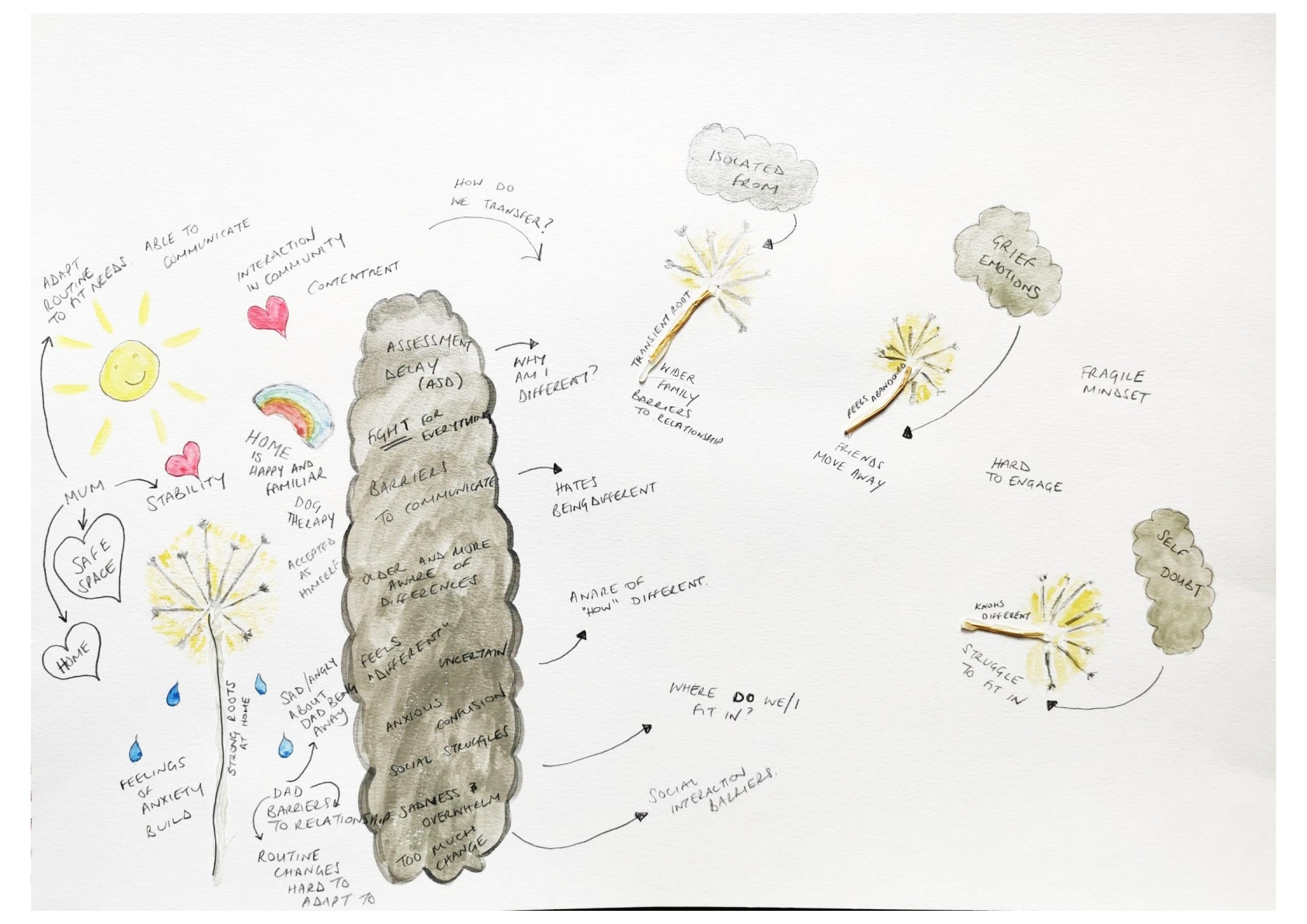

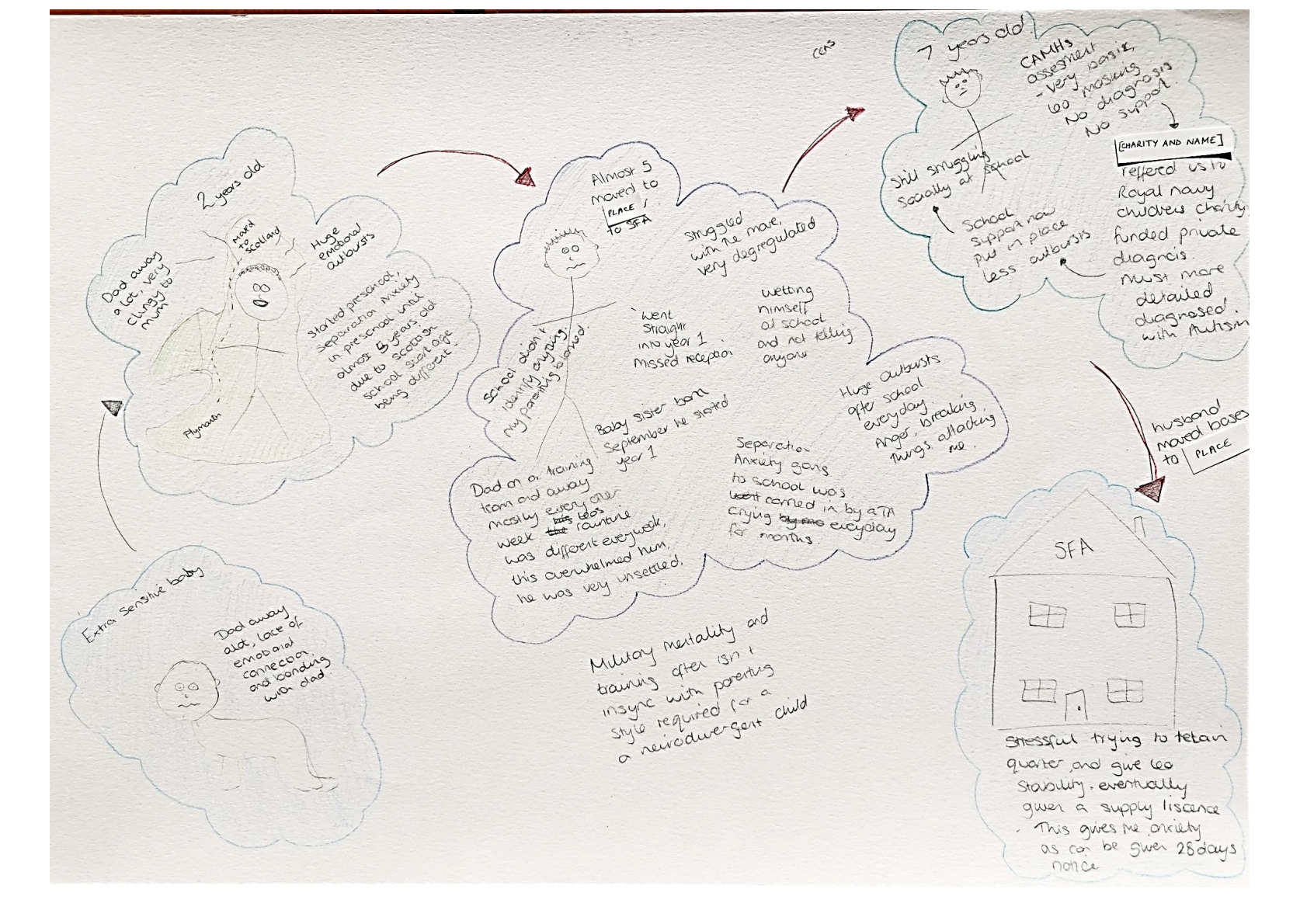

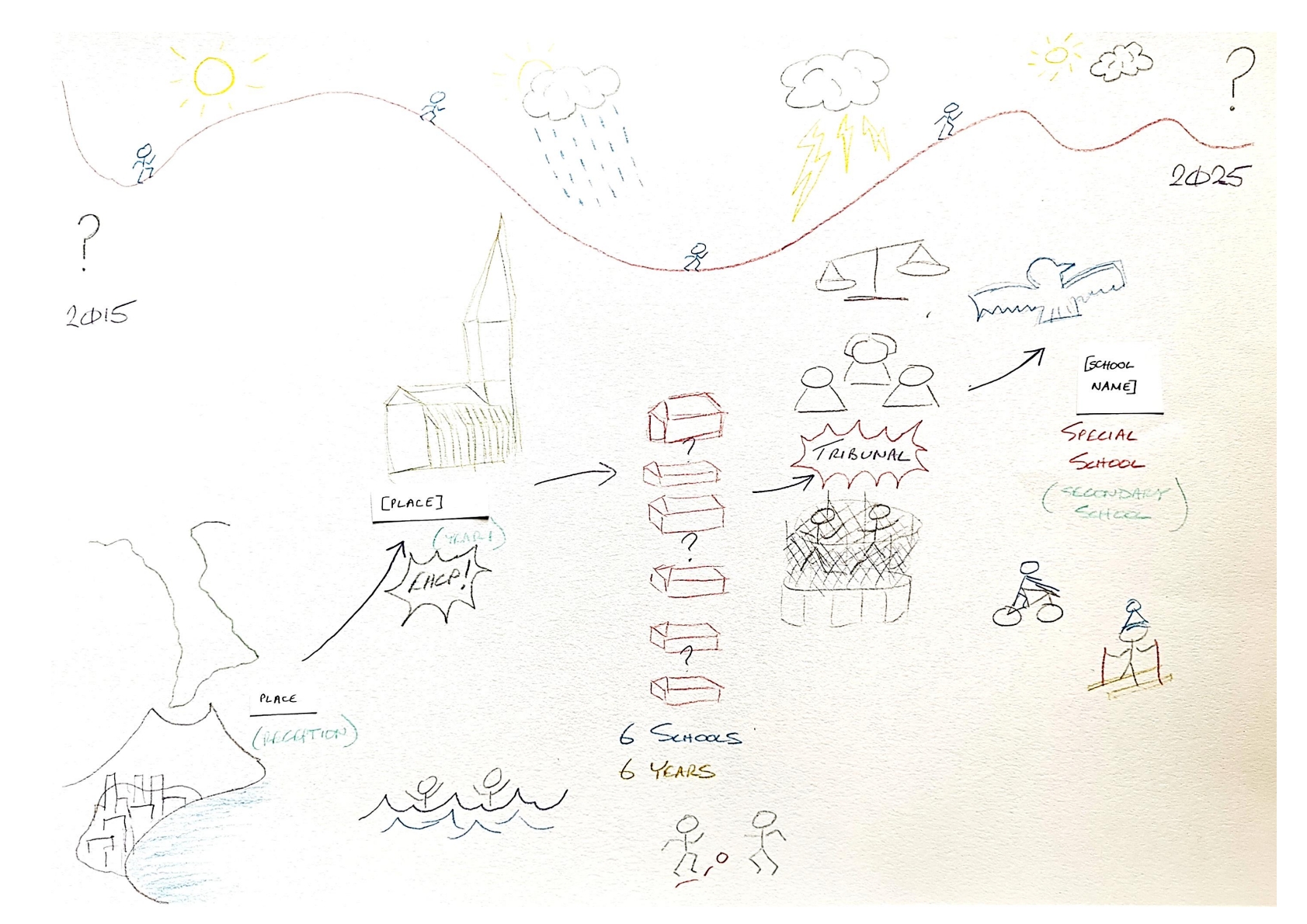

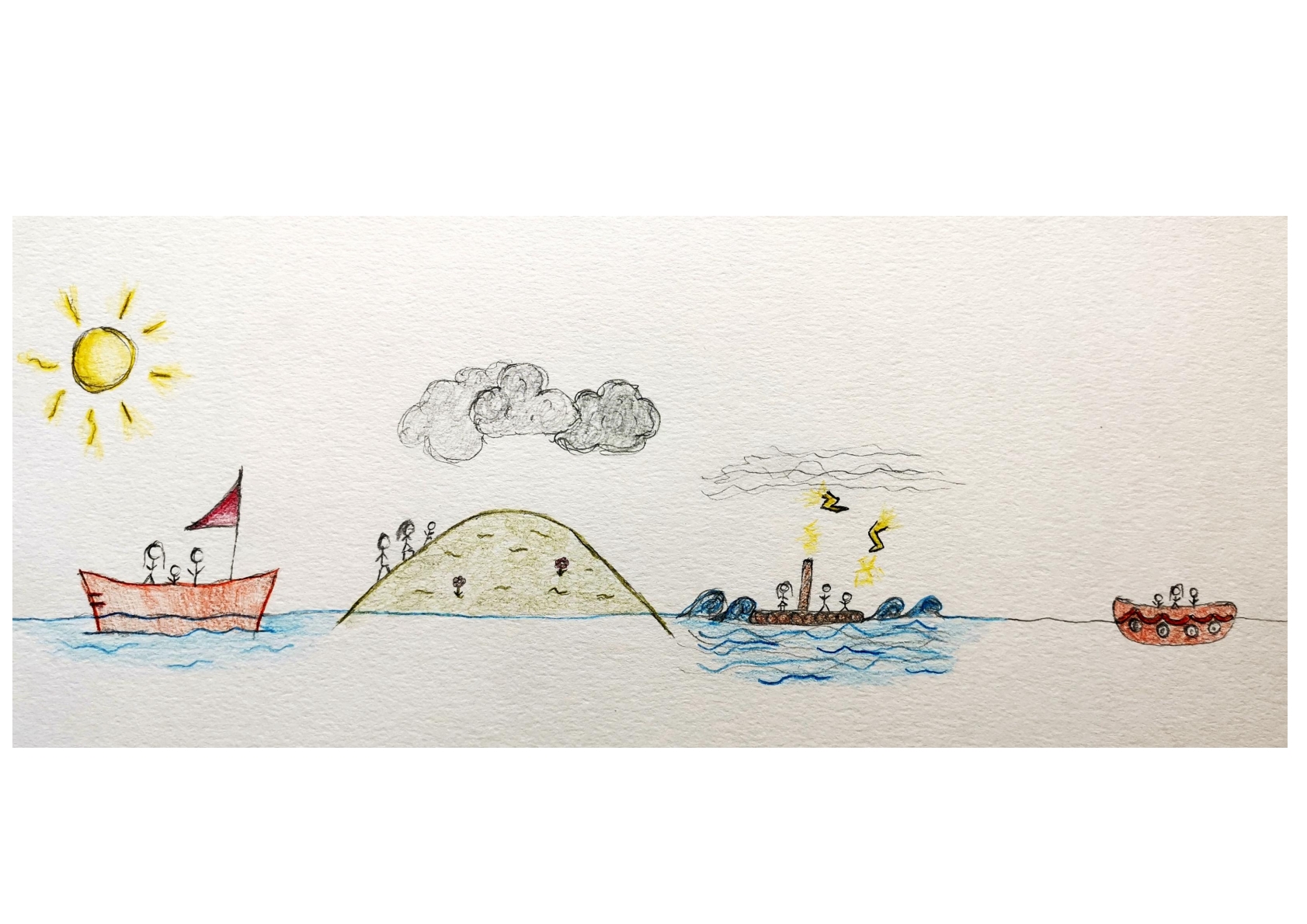

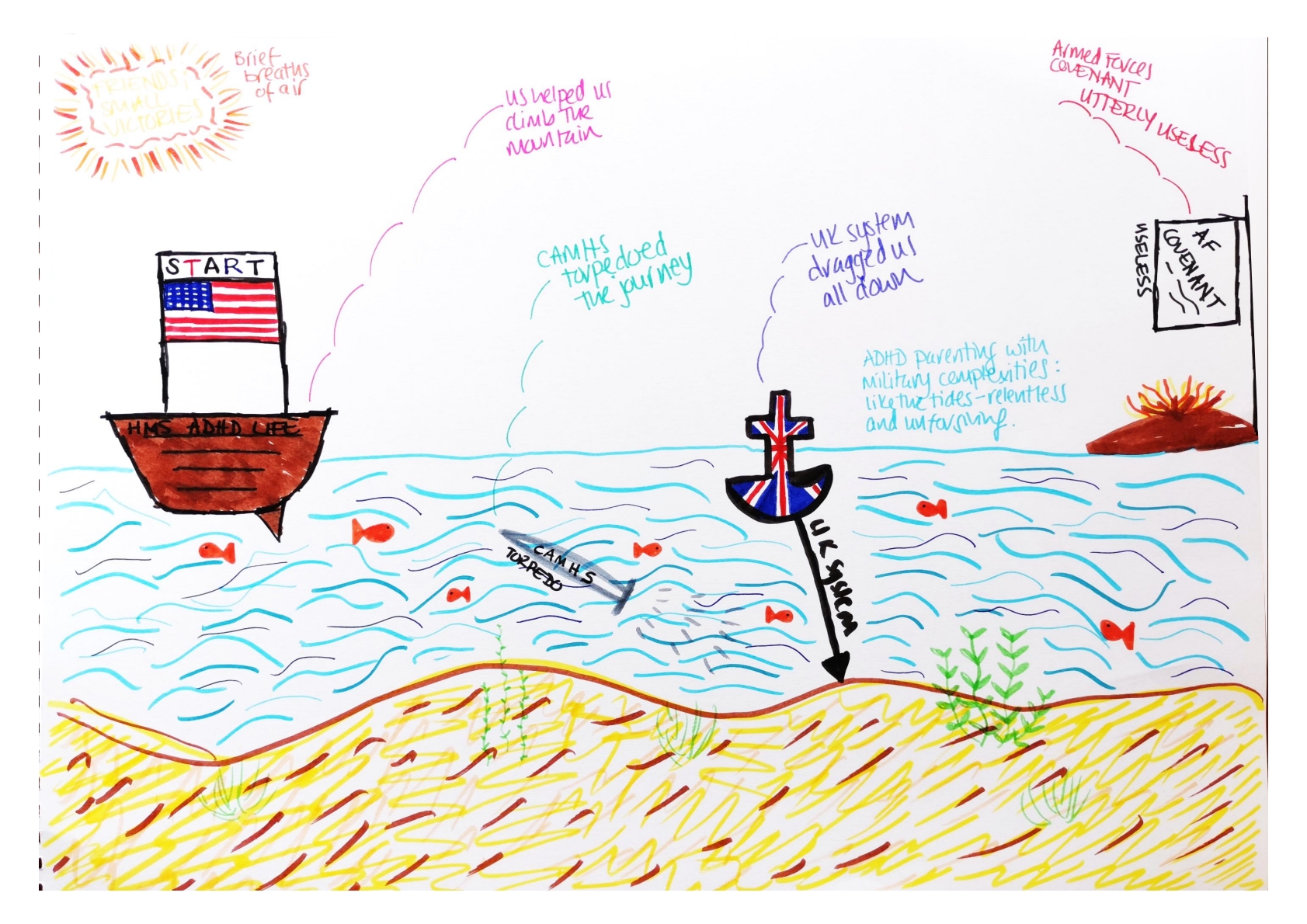

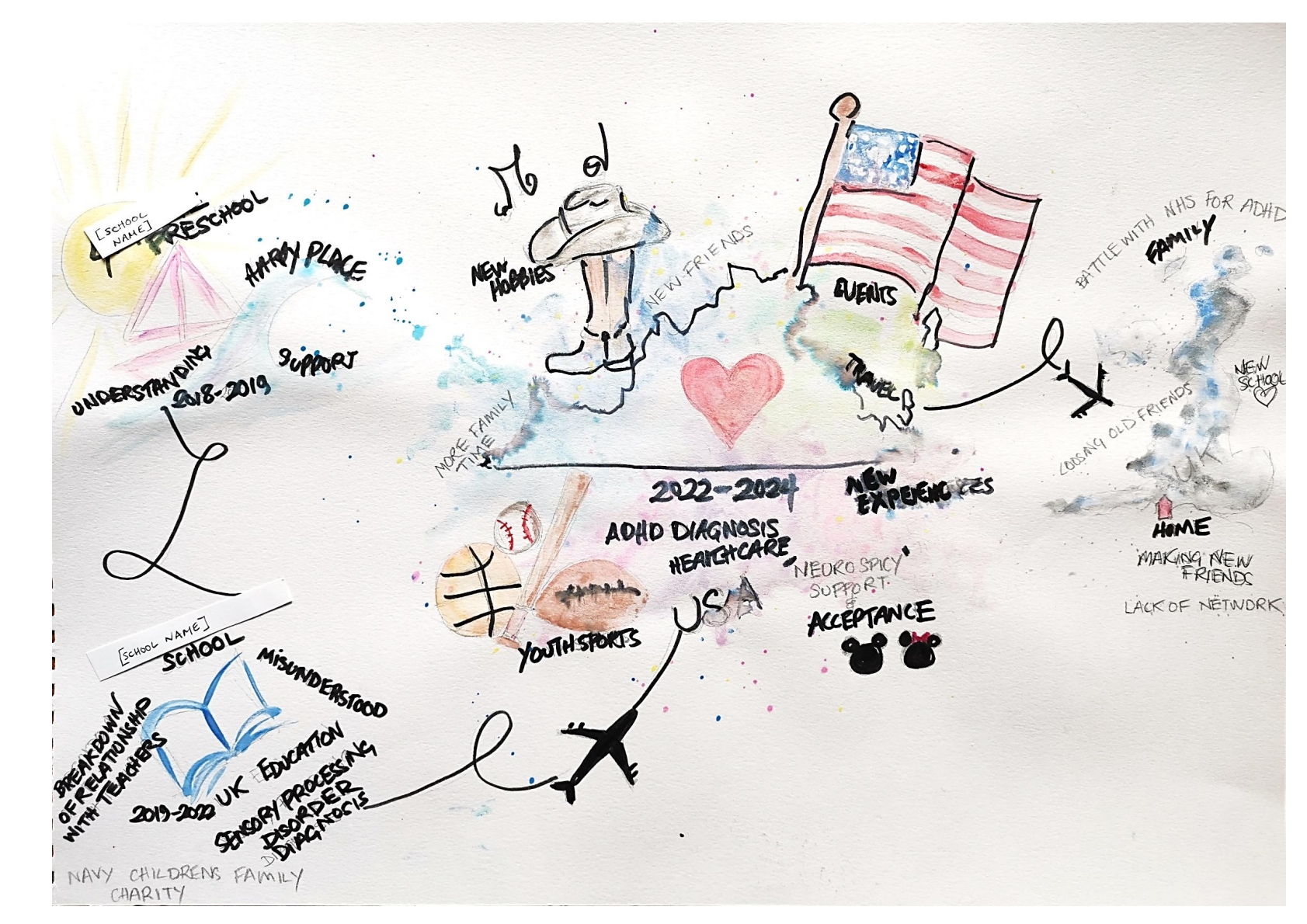

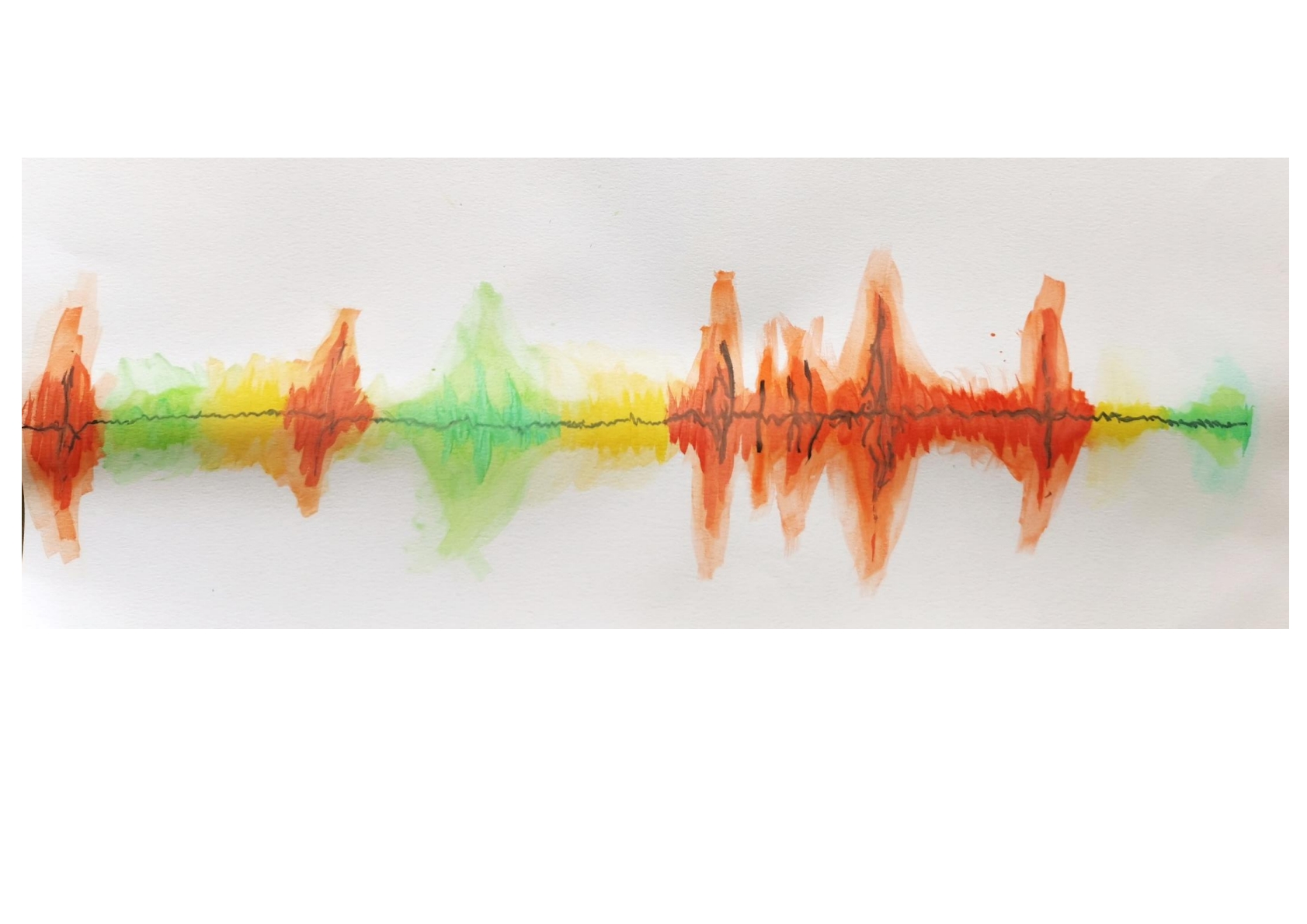

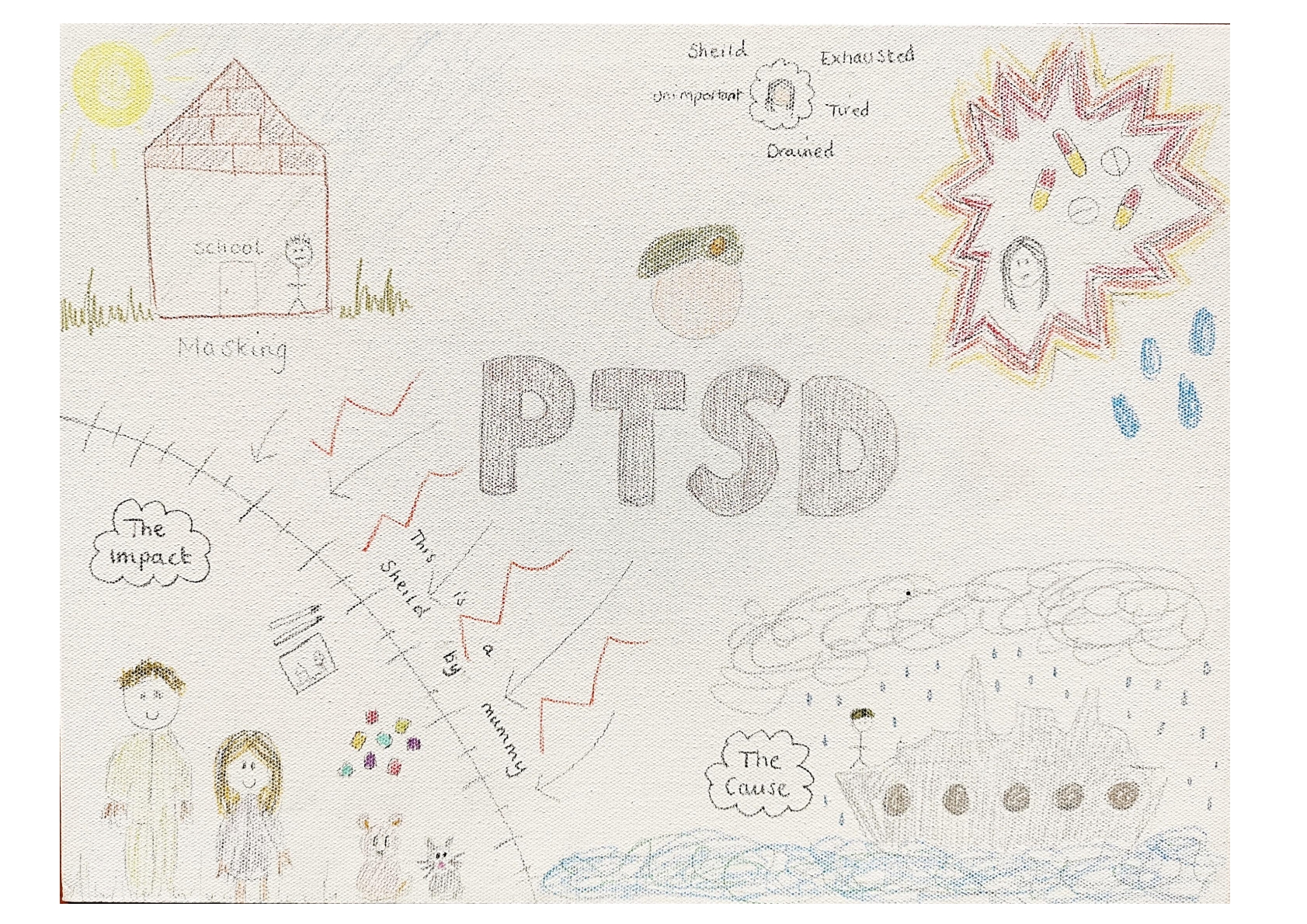

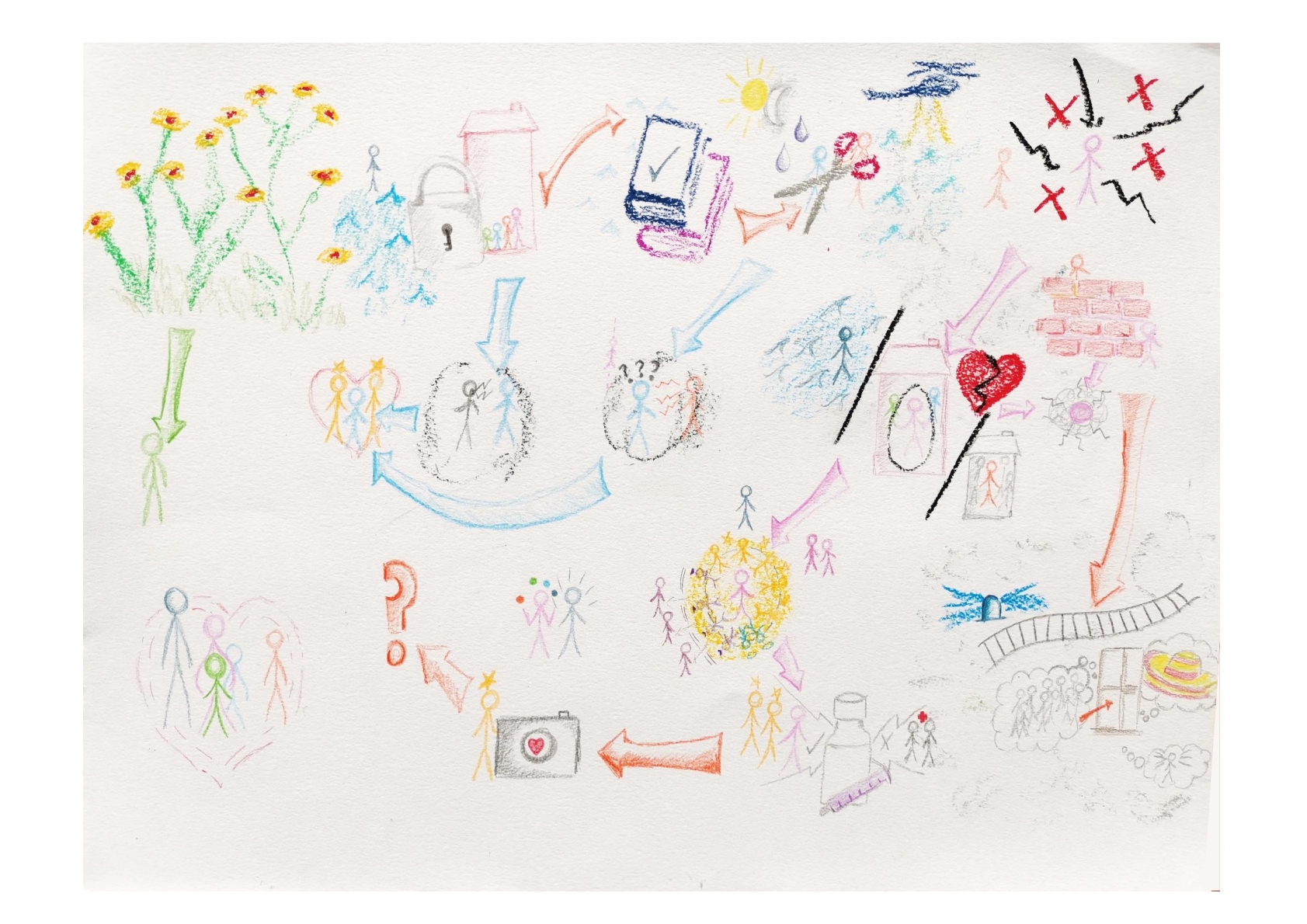

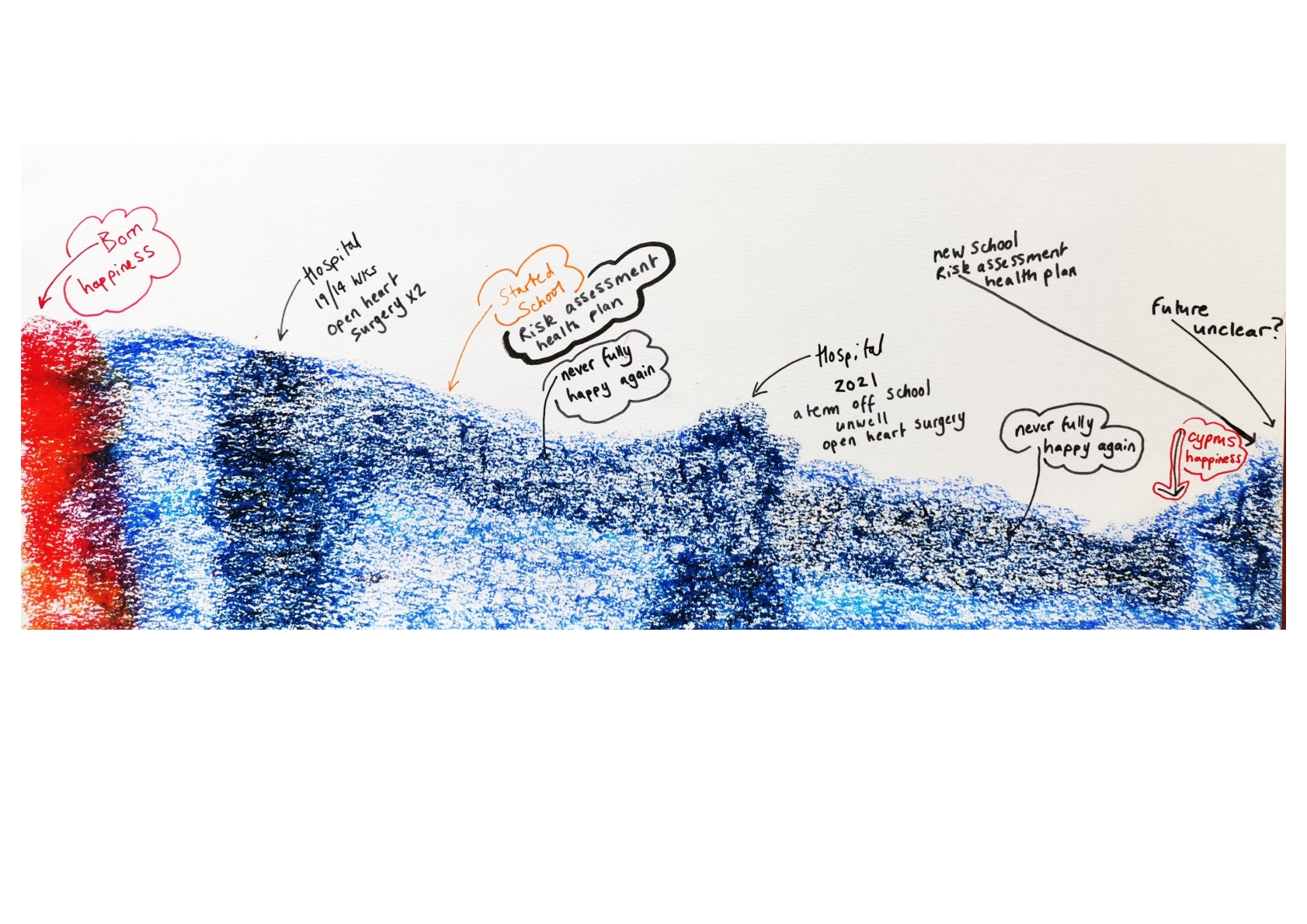

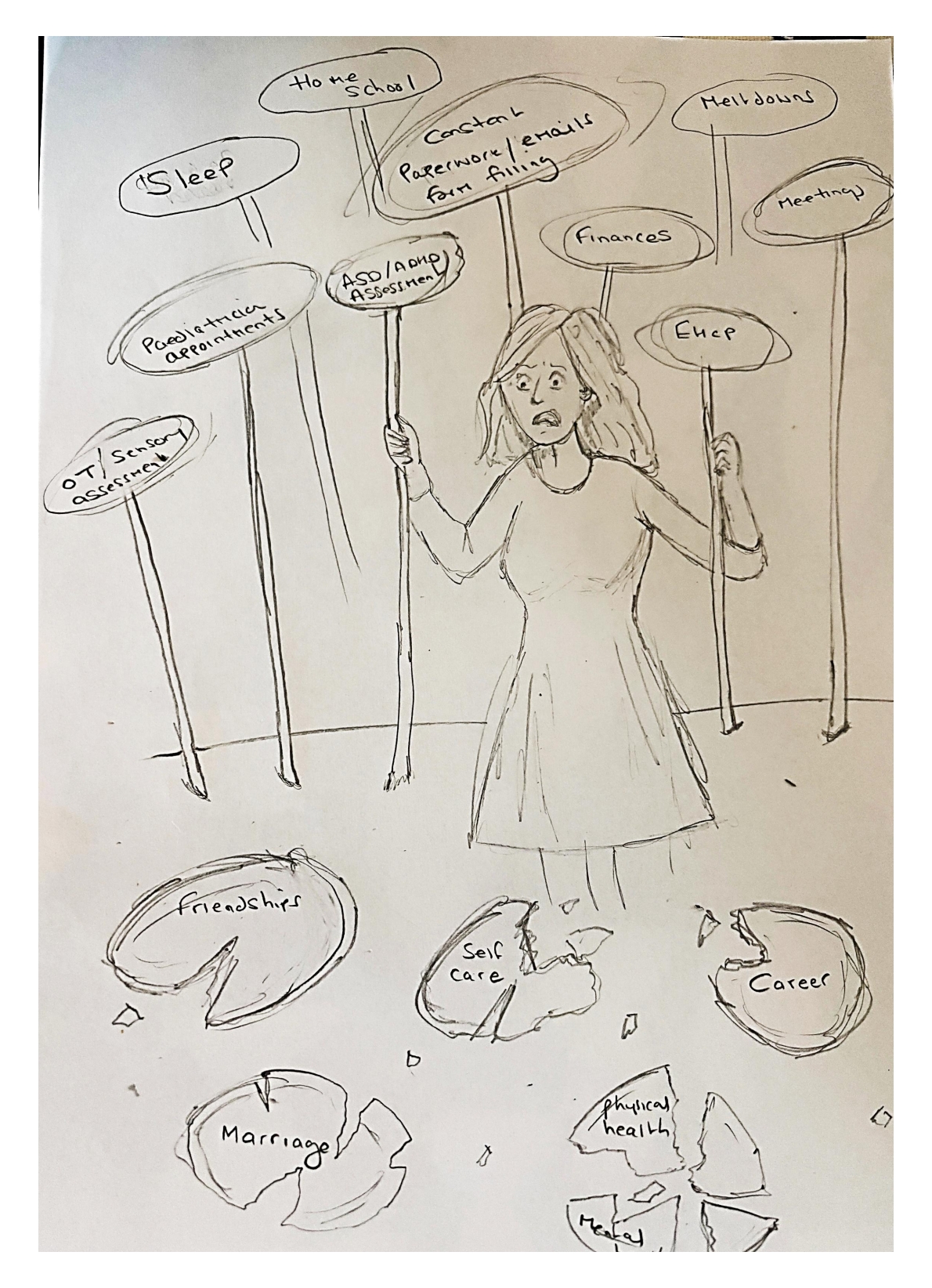

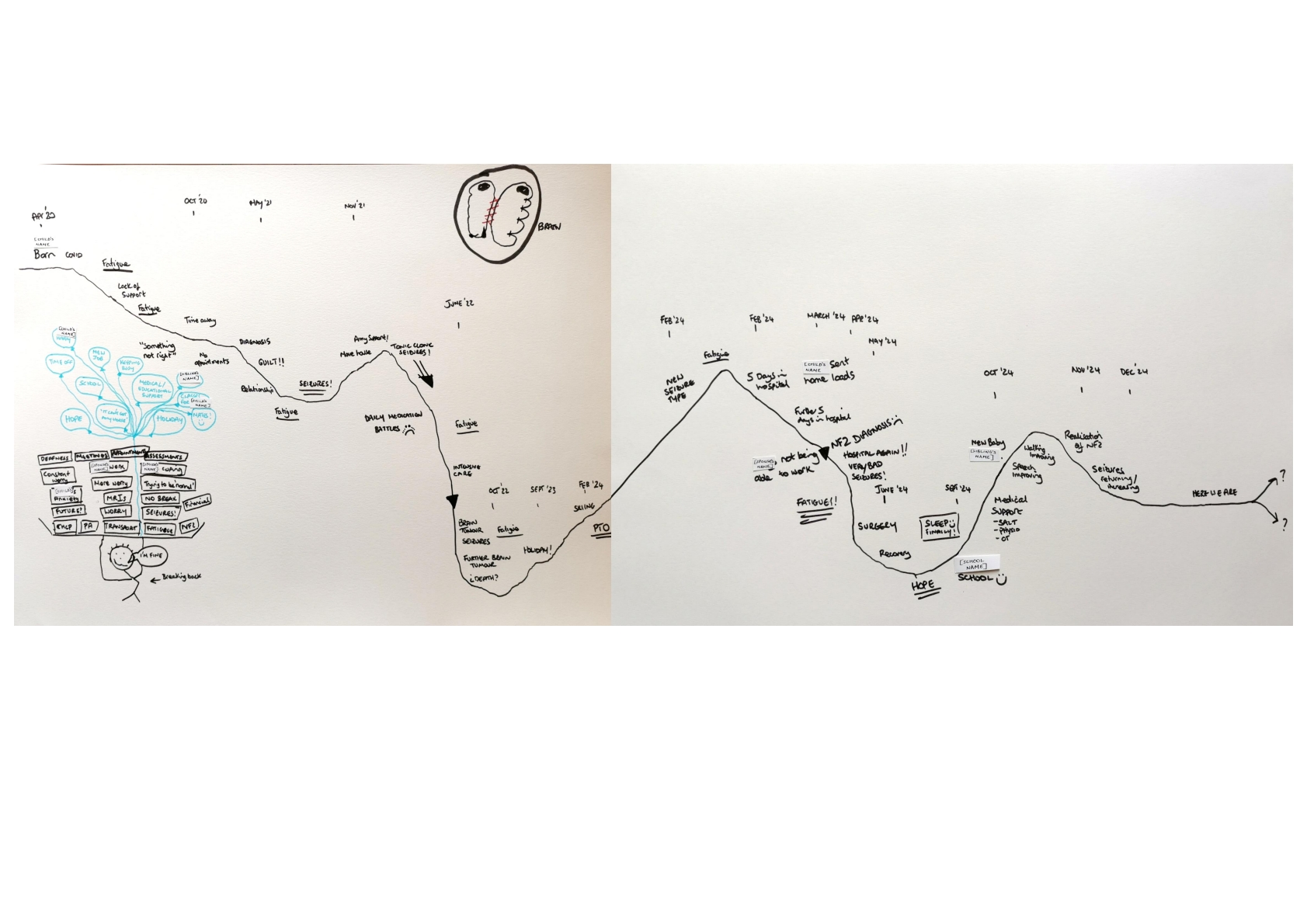

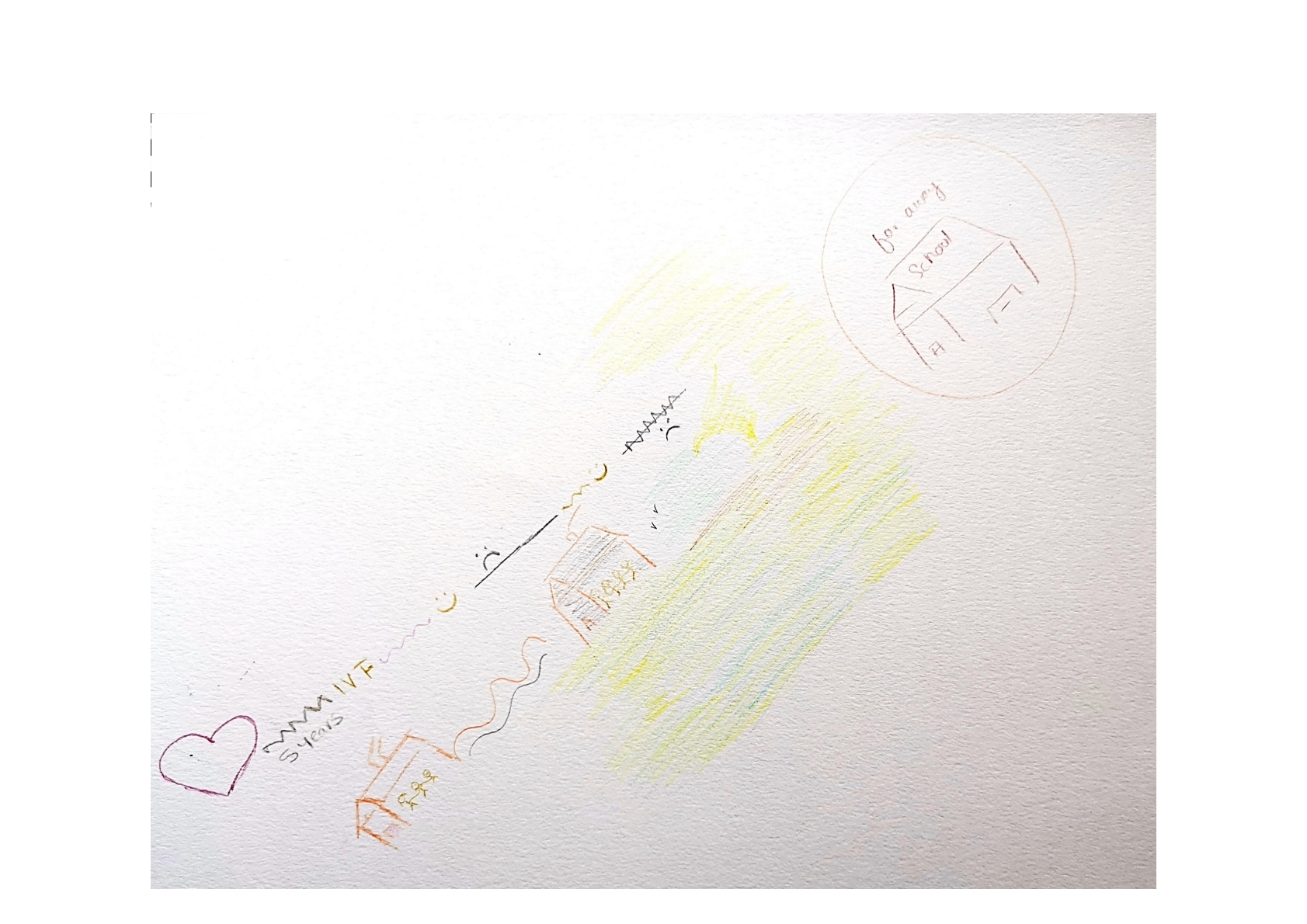

The images on this page were created during art workshops by parents of Service children with additional needs, and the quotations are their own words.

Select an image to enlarge it.

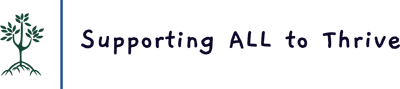

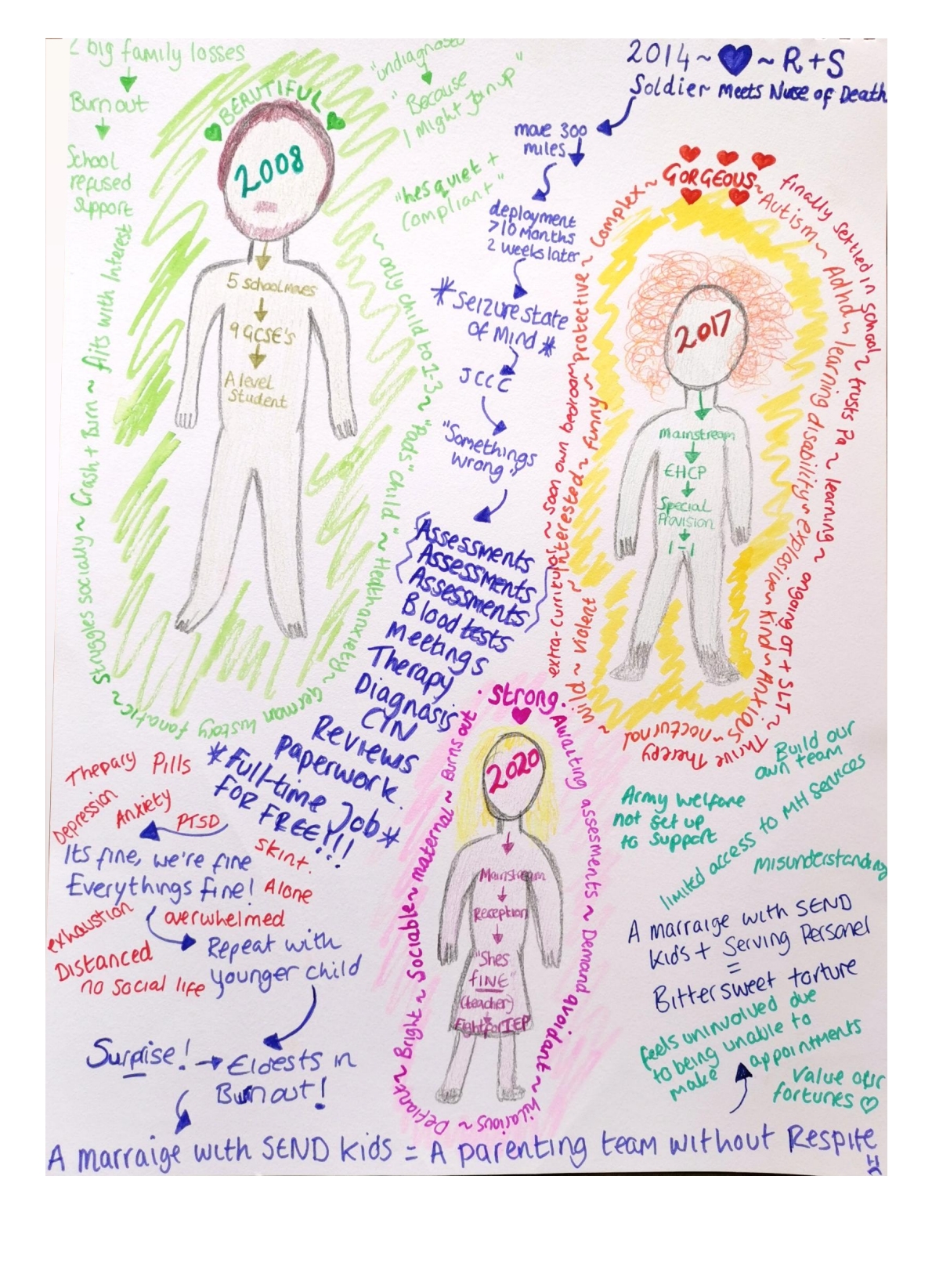

We’ve got depression, anxiety, PTSD from the seizures, therapy, pills, exhaustion, distance, no social life, overwhelmed, alone, skint.

And that’s the reality of living with a child with SEND, I think.

A marriage with SEND kids is a parenting team without respite. And a marriage with SEND kids and serving personnel is bittersweet torture.

I don’t think people, unless they’ve got a military connection or have lived that life, actually understand the gravity of it… it impacts absolutely every aspect of our lives as spouses, their lives as children, there’s not a single thing it doesn’t touch.

Unless you’ve lived that, you don’t have a clue.

I think you’re almost prejudiced AGAINST because you’re a military family.

I didn’t have any understanding of where this was going to take us, and the lack of support that was available, the lack of understanding for her needs, the resistance to even contemplating and understanding her needs.

He was in mainstream school, beautiful little village school.

Beautiful teachers, caring, nurturing. Kind students who accept… his quirks and differences.

But mainstream school wasn’t designed for him.

Trial and error approach to school placements:

It was like trying to put a circle in a box, right?… But he had to go through the trauma of seeing it through to see if it works.

He was an emotional wreck… He wasn’t facing going back in. I was getting school refusal. I was getting anger. I was getting tears.

You’re not listening. What are you not hearing me say? How many times do I have to say this?

Or am I just a mother, and therefore my… narrative doesn’t matter, because I’m not a professional?

I’ve lost count, the amount of times I’ve been told as a parent, ‘Well, we wouldn’t just take your word from it because you’re not a professional. You don’t know what you’re talking about.’

Very easy just to say, ‘Well, they’re Service kids, so there’s something wrong with them’. You know, ‘They’re quirky, they’ve got all this interrupted learning.’

I think that it’s a bit of an excuse, and it stops, perhaps, our educators and those who are there to support our children and young people, I think it stops them just scratching past the surface, and maybe finding out a little bit more.

He came home for the first couple of months, just a little bit more broken every day, and he would sit on the kitchen floor and sob his heart out.

One of the teaching assistants says, ‘Well, the thing about military kids is, you know, they just get on with it, don’t they? They’re really resilient.’

And I just looked at her and I just thought, ‘Okay, I couldn’t disagree with you more. For some children, it’s like that, but for some children, it’s horrendous.

For at least 10 years he was away 100 days every year…. [One time] he went [away] for nearly 10 months, 264 days. The kids didn’t even know who he was when he came back. No idea.

Whenever concerns were raised, school blamed deployment and refused to look deeper until my daughter’s mental health became concerning for them.

The period between being given the posting and the move actually happening was always difficult as it would create anxiety with not knowing where he was going to be living.

My son loved school and loved learning and begs me to go back to our last location and I can’t do anything.

Moving around:

Until I have an actual address, I don’t even know what council I need to go and apply to [for a school place], and then Council turn around to you and say, ‘Well, until you’ve actually moved in, we can’t do anything… And we’re not giving you a place.’

I do think there is something about Service families and the local authority perhaps thinking “Why should we support, and how long are they actually going to be here?’

And I think that has affected a lot of the services we’ve been able to access.”

They said, ‘You’re gonna have to start the process again.’

I said, ‘I absolutely refuse. Like, I know the waiting list’s long, but I’ve been doing this in two different countries. I have every bit of paperwork.

Like, there’s absolutely no way. He needs a diagnosis.’

In all of our journeys, an overseas medical system was so much more efficient, simpler, helpful, more efficient than ours.

And it is a complete disgrace. This is why we’re supposed to have an Armed Forces covenant.

Now we’re in the system, so to speak, you know, with education and everything else, we don’t want to move again because it’s just so detrimental… You work so hard to get all the support for your child. We don’t want to move again and then have to start all over again.

[My husband], potentially, would turn down a promotion to be able to stay here – or sign off.

He was on the front line…. And here he is, at the far end of that service. And nobody gives a damn about his children.

The Army’s approach is ‘Keep calm, carry on. Get on with it. Suck it up, buttercup… This is what you signed up for.’ It’s like, ‘No, no, no, hang on a minute…. I married him, I didn’t marry the Army.

Now the [military] knows more about mental health, and it’s taken a lot more seriously.

But equally, we’ve got the aspect of how men will deal with their mental health… you know, they’re like, “Nah mate, just get on with it.” And it’s a very toxic masculine environment…

Going to someone’s office and saying, ‘I need your help…’ it’s quite a tough thing to do, especially if you’re a junior rank and it’s a really busy captain.

Not saying that they’d be negatively received. It might be, but the perception would be that you might just get told to get a grip. And then you go home and you’re struggling. Your family’s struggling.

Obviously, we’ve come here. Again, living somewhere I don’t want to live. Don’t have any support, no family nearby… It’s shit. I hate the military… Want [husband’s name] to leave so badly.

I absolutely hate everything about them as an organization. I don’t think they’re supportive. Service need. That’s all they care about.

I had a full breakdown in their office. I was like, in tears, and I was just like, “I feel like I can’t be a good dad, a good husband and do this job with two additional needs kids. I don’t feel that I can do this.”

And I think the right thing for me to do is to leave the job.

Why isn’t it all coming together? Why are we all on our own, going through this minefield?

Because unless you literally hit rock bottom and you cannot cope and you are in crisis, then nobody helps you.

It just blows my mind how little it makes sense.

It all depends on your chain of command… My husband’s current [line manager] is fantastic and he gets it. His previous chain command held it against him and would remove him off courses.

Pride in the Army’s great, and most of us do have that.

But I think sometimes we all need to just put the

pride away, put the boots to one side… and all of us

just talk.

And remember that there’s kids in the middle of this,

who are real people.

The teacher… said, ‘How can we make this work for [her] in the classroom? What can we do?… Where do you want to sit? Is it too busy? Do the displays bother you? The sound? Who do you want to sit next to?’

His education has bounced back and he enjoys going to school now.

The kids are like, “My dad’s a Royal Marine.” And I’m like, “Yeah, that is something to be proud of.

The small victories are kind of like, you know, brilliant breaths of air in amidst, you know the relentless tide…

There’s a lot of times when it’s been, like, quite dark, with the kids and Husband away and stuff. And this [families’ centre]… when I used to bring [Daughter] here, was absolutely my light.

There’s nothing I found more moving than when a teacher or, you know, a healthcare person takes the fight for you. It’s astonishing and unfortunately rare.

![No school for 2 years but now she's thriving Images of two daughters labelled E and C. Balloons with birth details, Covid in black/yellw 'danger' sign, box labelled 'Nursery', storm symbol, sun labelled [A] School, bullet points and labels throughout. Cloud shape with 'worries'.](https://sattproject.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Artwork-landscape-A2_Part1_1.jpg)